Creating believable characters is hard and showing how they change emotionally during the course of the story, harder still. Sometimes I feel like I need a degree in psychology to get it right.

In my last two blog posts I discussed character arcs, also known as the internal journey, or in the vernacular, emotional baggage. We all have it, but often it’s human nature to bury our heads in the sand and not think about it too much. However, examining our own inner psyche and the journey we have made through life, may help provide us with a better understanding of the characters we create.

Dara Marks, in her book The Power of the Transformational Arc, maintains that in order for a writer to be successful, they not only have to know their story, but also know themselves. She says:

“A natural story structure is one that reflects the true nature of the human experience.”

Or as Aristotle put it “Drama imitates life.’

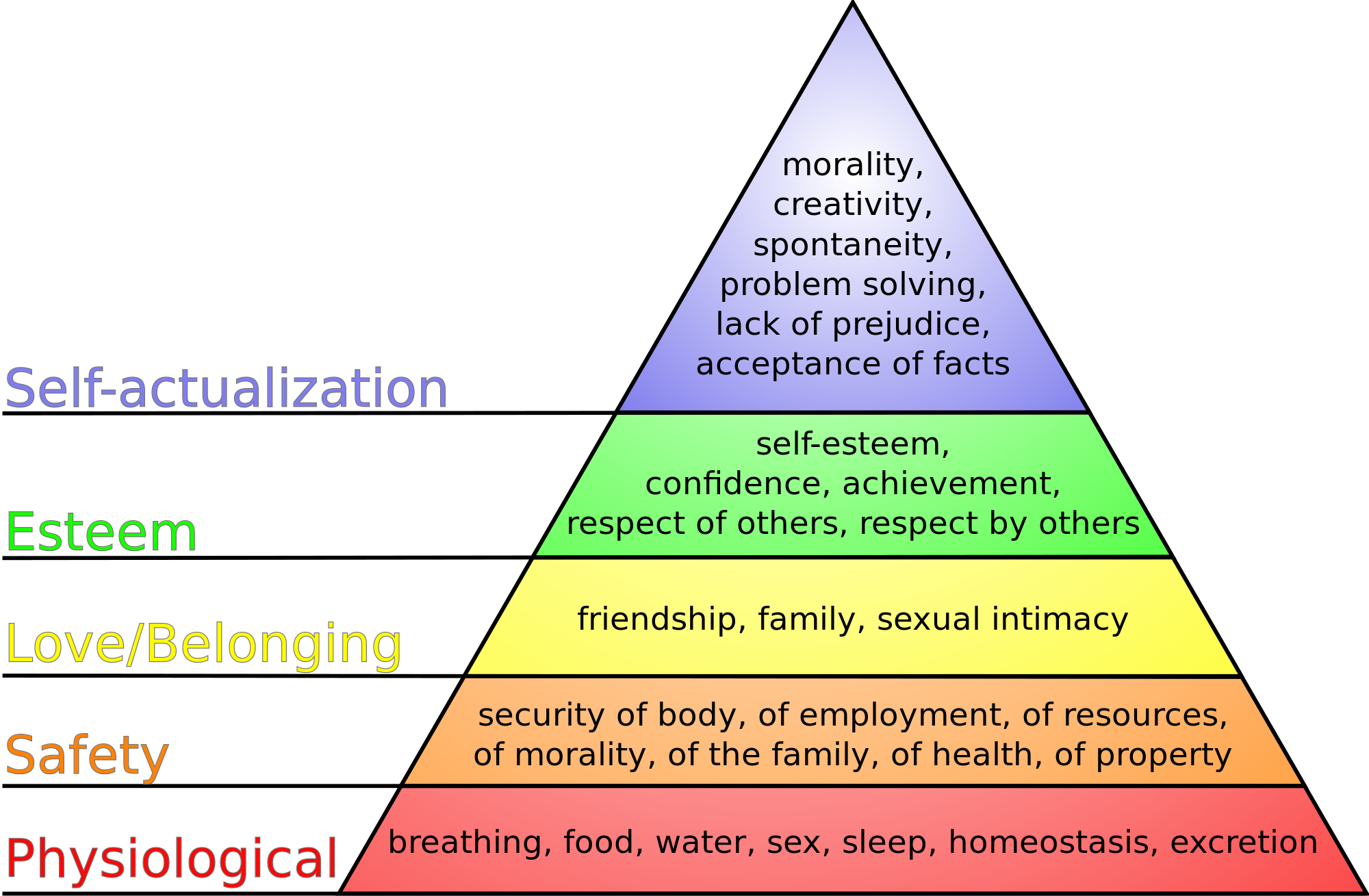

One of the first things I learned about story structure was that every character should have a goal, and this in itself is a reflection of the human condition. Psychologist Abraham Maslow describes humans as “wanting animals”. As soon as we get one thing, we move on to wanting something else. To show how we prioritise these different wants, he developed the Hierarchy of Need.

At the bottom is the basic need for food, shelter and safety, we then move on to want love, self-respect and finally, self-actualisation. In character-driven fiction, it is these latter needs that often form part of a character’s inner journey whilst action movies may focus on more basic needs, such as safety.

Whether a story is character or plot driven, our characters will face obstacles which will force them to make decisions. But sometimes it’s difficult to know which path our heroines and heroes should take. Whatever they choose to do, it must be believable and consistent with the background we have given them. That’s when it can be helpful to draw on personal eperiences.

At birth, inherited DNA aside, we are pretty much a blank canvas. It is what happens next that creates character such as parenting, upbringing, schooling etc. All these factors will influence the type of person we become, how we respond to adversity and the decisions we make. Our characters need to evolve in the same way.

My favourite TV programme at the moment is First Dates where single people of all ages and background are looking for love. Some talk about their parent’s bitter divorce, a cheating ex, or tragically, a loved one who has died. These experiences have made them reluctant to open their hearts because they fear being hurt again and to love makes us vulnerable.

If we can similarly understand our own vulnerabilities and where they come from, it may help make us become better writers and in turn, create believable characters.

Maslow says: “human motivation is based on people seeking fulfilment and change through personal growth.”

It could almost be a line from a writing craft book.

Lizzie Hermanson is a wife, mother and talented procrastinator. She writes contemporary romance when her cat isn’t hogging the keyboard and loves Happy Ever Afters. Find her @lizziehermanson